Jay Gertzman

Goodis' Varied Femmes Fatales

Femmes Fatales: Celia and Vera

Femmes Fatales: Celia and Vera

Pulp According to David Goodis

By Jay Gertzman

The variety of dangerous women in Goodis is a sign of the weird fascination he and his readers have for perverse intimacy. It is inevitable for the protagonist of the novel to find the femme fatale irresistible, especially b/c he senses she may indeed paralyze his will. The novelist depicts a world where men are drawn into a web that they may or may not even want to escape from. It's Philadelphia Gothic.

MADGE in Dark Passage: The more this person likes a man, the more she pursues him until he wants only to get out alive. That’s the case with her former husband. She wants Vince, the protagonist, who was married to Gert when they first met. The attraction is mysterious. She likes his decency, courage, perseverance, intelligence. Contrarily, she is mad with possessiveness. One reason for Vince’s daring escape from prison, where he is serving life for killing Gert, is to prove Madge killed Gert, and later, Vince’s best friend, Fellsinger. This she did so the cops would think the fugitive, Vince, did it.

Madge befriends Irene to tell her Vince is a vindictive killer. She needs to destroy Irene's affection for Vince so she can have him under her own thumb.

Vince does track down Madge. She knows Vince cannot reverse the verdict of his killing his wife unless Madge testifies. Now Goodis reveals the uncanny power of this "orange enchantress." She jumps to her death, so that he’ll never be able to prove his innocence. (The movie had to make the fall unintentional, b/c the guardians of decency felt suicide was too shocking for a mass audience). Goodis describes her falling as “her gold inlays glittering” and the "billowing of her bright orange “hair, coat, and slacks.” See the image above of her knocking at the door of Vince's worst nightmare.

CLARA in Behold This Woman has the power to humiliate the men in the story and terrorize the women. Barry and Evelyn want to be together, but her ability to shame and unman make them unable to get together. Clara has the same uncanny controlling traits, and the “fallen angel” sinister character, as does Madge. . One of Clara’s earlier victims says: “The forces of evil are stronger than my own will.”

GERALDINE in Of Tender Sin is fascinating to Al Darby b/c she looks uncannily like his sister, Marjorie. Al and she were very close. At 12, he lost his mind and raped 15-year old Marjorie. Their parents sent the girl away, and Al tried to repress the episode.

Then he met platinum blonde Geraldine. Al and Geraldine’s mutual lust is more luridly described than that of the incestuous episode: “It was like crawling through a furnace, in the depths of the orange glow down and down to where the fire was hottest. Then there was her wailing laugh that climbed and climbed until it broke and her arms and legs were limp and her eyes were closed.” [there’s orange again, night quite a raging red, or glowing yellow]

Al leaves her, but 6 years after marriage, he has a harrowing dream, beckoning him to a “long, long road” that ends at Geraldine's house. She has not changed her appearance. Her cynical fatalism (“the world needs another flood”) has hardened, and she has “a new boyfriend, Charlie.” She means her cocaine habit (she’s also a pusher). She brands him, drawing her name in his chest with her zombie-like fingernails. “This time you won’t get away.” Talk about doomed romanticism.

Her description has biblical implications. Goodis seems to pattern her after Lilith, the first mate for Adam, who pleaded with God to be rid of her. Al has gotten mixed up with the first femme fatale. Lillith insisted on equality with Adam, as Satan wanted with God. Banished from paradise long before Adam, she married Samael, a fallen angel, and was devoted to preventing childbirth, i.e., ending the human race. Geraldine’s misanthropy is implied in her selling cocaine in schoolyards.

Equally weird is her “cackling,” which substitutes for laughter.

Another allusion may be to Double Indemnity’s Phyllis Nirdlinger (Dietrickson in the film) , a symptom of Walter Neff’s deep-seated resentments, and a death-spitting cobra whose bridegroom is Death.

Late in Of Tender Sin, Al expresses his desire to stay with the sadistic Geraldine, who “ruled without mercy. … And most of all he . . . the pale green eyes and the platinum blonde hair.” This implies that his beloved sister and Geraldine are doppelgangers: opposites, one loving and passive and the other all-consuming. They are symptoms of what bedevils Al, his shame and need to be punished. In other words, he is still trapped in his desire for his sister.

One of the Gothic elements in these three novels is the power of the femme fatale to feed upon the intertwined fears and desires of the protagonists. That they can do so gives them an unearthly aura, like Keats' Belle Dame Sans Merci, or Lilith, or even Norman Bates' mother, who is never seen b/ c she is inside the protagonists' head.

Femmes Fatales: Celia and Vera

Femmes Fatales: Celia and Vera

Femmes Fatales: Celia and Vera

Pulp According to David Goodis

By Jay Gertzman

Celia, in Street of No Return, and Vera, in Somebody's Done For, are women that Whitey Lindell, and Calvin Jander, respectively, cannot live without. Without them, the men “have nothing in their lives.” That they do not come together is equally tragic for the females as it is to the males.

Eugene Lindell sees Celia dance, and refused to give her up. Sharkey pleads with him to leave town. He cannot; what she promises is unfathomably magnetic to both men. It would be intolerable spiritual deprivation to lose her. As we know, it is Whitey who loses, and loses his means for making beautiful song also. He loses his “backbone,” drinks rotgut, and hangs out on the steps of a skid row flophouse.

Describing Celia dancing at a stag party, Goodis tells us there was nothing sensual about what she did. Far from what would be expected from a former hooker, it “had no connection to matters of the flesh”; the men watching felt what they had never felt before, a spiritual challenge to recognize her soulfulness and approach it reverently. They have no context for what the dancer was expressing about refinements of prurient lust into something not roller-coaster exhilarating, but more precious: a mysterious peace and forgiveness. They were anxious for the next dancer, whose routine would be “very raw, smutty and ugly to get them back to earth again.” They idolize the women too much to want intercourse with them. Celia had made them “feel like worms crawling at the feet of something they didn’t dare to touch.”

Freud termed such a situation “degrading” as well as common. Sex can be desired only with sluts. Love is too much like prayer to have any earthly content. One writer characterized this split between the holy and the profane as producing a “poisoned embrace.” Another used the term “psychical impotence.” It’s as deep in the Judeo-Christian definition of good and evil as the need for a messiah. It reduces the female to a “symptom” of male desire, or idolization.

In Somebody's Done For, men addicted to driving hours to see Vera dance say, “I can’t stay away from this place.” But it is the “worst pain there is. It’s the pain of craving the unattainable.” These statements express desire and fear of Vera as a kind of goddess they do not know how to worship. To get close enough to be intimate would mean a complete take-over of their energies, “. . . the feeling that [they] had been captured, rendered helpless.” Al Darby, in Of Tender Sin, thinks that this infantile state is what he really wants for the rest of his life. He’s tough enough to rip off a thief’s scalp, but inside, he’s really still a mamma’s boy.

Calvin Jander is no jellyfish. He and Vera love each other completely, that is, sexually and emotionally. Vera says, “It’s real, all right. It’s just as real as that moon up there.” It was fated for sure, as is clear from words such as “ordained,” “mystical,” “absolutely,” and “moon,” which in several fictions means ultimate entrapment, not heavenly peace. Vera cannot be without the man she thinks is her father. Celia cannot be without Sharkey.

It may be wrong to describe Vera and Celia as femme fatale. They are passive figures, themselves controlled by false protectors themselves obsessively tied to the woman. For Vera, it is a childless criminal who kidnapped her when she was an infant. Celia is in the power of a killer mobster, the guy who says if she was not with him, he would wither away. It is the power of the women over the men that replicates the femme fatale concept. They are, as Slavok Zizkek says, “symptoms” of the perverseness of their worshippers, which includes emotional impotence.

If you remember Portnoy's Complaint, this is indeed the hero’s problem. He can enjoy sex (actually oral sex) with a non-Jewish girl, but when he visits Israel, with a beautiful Sabra he is impotent. Shame is built in—to the scrotum. Love, as we burden it with the “love is heavenly” conceit, becomes a fantasy harmful to happiness. That was why D H Lawrence’s definition of love was “sex in the head.”

Beyond Twisted Sorrow

The Requirements of Gothic Fiction

The Requirements of Gothic Fiction

New from Jay Gertzman

Beyond Twisted Sorrow describes rural noir’s roots in 20th century crime stories, and how it takes a radical new direction. My thesis is that this still-evolving genre revives the democratic ideal of America, indeed its envisioned destiny, drawing on an instinct for community as a coherent territory, “somewhere in that vast obscurity beyond the city.”

(Fitzgerald).

While 20th century urban noir often ends with a conviction that a cruel, inevitable fate overwhelms any attempts to escape injustice, rural noir looks to the vast western spaces for a contrasting possibility.

Writers such as Daniel Woodrell, Denis Johnson, David Joy, Annie Proulx, Matt Phillips, Chris Offutt, Rusty Barnes, Steph Post, S A Cosby and Richard Hood give to readers what seem at first to be wildly self-destructive protagonists who end up discovering a stable and viable existence, “Beyond Twisted Sorrow.” Some of the most famous of these are”social isolates,” who cannot themselves accommodate themselves to laws, traditions, and tastes of any community, but without whom the community itself would fall victim to criminal power. The most famous are Shane and Huck Finn.

Essential to this kind of writing is the present-day decline of Appalachian, Great Plains, East Texas, and Deep South towns, ranches, and farms. Corporate-level crop growing, meat packing, and food preparation make generations-old endeavors obsolete. Drug dealing, especially in view of the Oxycontin racket and its aftermath, has destroyed many rural southern and Appalachian communities. Food and medicine becomes scarce, infrastructure decays, and hospitals close. This is the “heavy load” that unexpectedly fuels a unique self-awareness and community spirit in many novels.

Readers may know thr film Nomadland, a study of rural people who have substituted van living for homes lost in the financial crash of 2008. Last year, it won Academy Awards for Best Motion Picture, Best Director, Best Actress, and Best Adapted Screenplay. It is the focus of my final chapter.

The Requirements of Gothic Fiction

The Requirements of Gothic Fiction

The Requirements of Gothic Fiction

By Jay Gertzman

The term “Gothic” is a favorite blurb on crime fiction book covers. But many of these yarns are grotesque potboilers; true gothic is difficult to produce. Writers who meet the criteria include Harry Crews, Annie Proulx, Daniel Woodrell, Chris Offutt, Joe Lansdale, Larry Brown, and Denis Johnson, combining mystery, horror, the demonic, extreme violence, and dynamic responses to survival. They approach the power of two masters of country gothic: Flannery O’Connor and Cormac McCarthy.

The tools of the gothic writer include multiple points of view; archetypal hunters, poverty-beset towns, and hard-nosed lawmen; the passing of time; the merging of human with nature’s actions and reactions; the weird indeterminacy of motives and events; the remote, grotesque yet communal setting; and nightmarish acts both instinctive and calculating.

De Sade portrayed the gothic storytelling of his own iconoclastic time as “the inevitable product of the revolutionary shock with which the whole of Europe resounded.” Country noir also delineates shock: loss of land and home; entrapment in drugs, alcohol, and other engines of despair; inaccessibility of health care; and legal protections from racketeering.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Tom Franklin’s Southern gothic novella Poachers brings together dirt, blood, murder, and retribution by a mysteriously implacable representative of the power of Law. The poachers are three brothers, for whom hunting is their life. They are illiterate, almost feral. Speaking in gestures and grunts, they are as much part of nature as the animals they kill. Kent, Neil, and Dan live deep in the woods, near a community of decaying shacks. A tyro game warden one day arrests the brothers for poaching. Uneasy, the warden shoots one of Kent’s hunting dogs. Kent strangles the lawman.

.

A chief gothic element of the tale is the eye-for-an-eye“justice”—or is it inevitable fate?—that befalls the three young men. Kent is strangled in what looks like a cottonmouth snake’s doing. Neil is blown to bits by dynamite: the same kind that the brothers used to kill fish. Dan, in his turn, is hunted down. Either a venomous snake, or revenge exacted by a Black man whose daughter Dan molested, causes the youngest of the three poachers to go blind.

.

All three events were the work of Frank David, retired game warden who had groomed the man Kent strangled. Frank was the archetypal protector of state game land; a force of nature: Frank “ris[es] from the black water beside a tree on a moonless night, a tracker so keen he could see in the dark, could follow a man through the deepest swamp by smelling the fear in his sweat, a bent-over shadow stealing between the beaver lodges…”

https://downandoutbooks.com/bookstore/gertzman-beyond-twisted-sorrow/

https://downandoutbooks.com/bookstore/gertzman-beyond-twisted-sorrow/

Gothic closure can signal a painful and sometimes eerie transformation . That might apply to blind, long-bearded Dan, silently walking in the same woodland he knew when his brothers were alive and poaching. If he cannot look over his shoulder at the presence of Frank the all-powerful warden, that only means he can experience him at a deeper level, as a cruel, murderous counter-force inevitably created by the poaching.

McCarthy's exemplary gothic novel, part of his Border Trilogy, clearly advertises its biblical universality. The bible itself has both noir and gothic passages, and at this stage of his career, McCarthy might be deemed a religious as well as crime writer.

.

He describes of the merging of human with nature’s actions and reactions, and stresses the sense of loss in the characters with the passing of years. Part of that is implied in the setting, near the nuclear testing facility of Alamogordo, NM. But the mysterious Mexican borderlands are where the most gothic events transpire.

.

His hero, John Grady Cole,is a model cowboy, the best horse trainer in the West. He is also a uncanny healer, and protector, of wildlife. He is in love with the innocent Magdalena, trapped in an expensive whorehouse run by Edwardo, a sinister example of capitalist wealth and power, who, paradoxically, also loves Magdalena. Gothic is all about the weird indeterminacy of motives and events. In a nightmarish knife fight in which Grady and Eduardo show instinctive and calculating skill, Eduardo slashes his initials in Grady’s thigh but Grady delivers a killing blow to Eduardo’s jaw. Meanwhile, however, Magdalena has had her thought horribly slashed open. Grady dies from loss of blood. In an Epilogue, many years later, Grady’s best friend Billy, after conversation with the Devil, finds a caring couple to take him in.

.

A chief aspect of gothic, as stated above, is its appearance when the culture of the writer is in traumatic decline. "Revolutionary shock" is the most profound experience it offers.

.

Copyright © 2022 Jay Gertzman, All rights reserved.

Rural v. urban noir. Response to "thou shalt not."

Rural v. urban noir. Response to "thou shalt not."

Rural v. urban noir. Response to "thou shalt not."

By Jay Gertzman

While the difficulties of forging satisfying human connections are clear in rural noir, the possibilities of a progressive communal future can be in the offing.

The effect of crime on citizens of a community has been a theme of American noir fiction since its inception in the mid 20th century. Stories about the power of mob bosses and racketeers are about how people survive forces beyond their making, and their control. Close cooperation between the upperworld, that is, a community’s respected political structure, and the underworld, drives the way citizens not only make a living, but live and die. It has been said that communities large and small need crime. That is how the economic, political, and social organization works. As the District Attorney told Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep, that is “how cities are run.”

The ability of vulnerable citizens to maintain self respect is described differently in contemporary country noir than it was in 20th century mass market crime stories.

David Goodis’ Street of the Lost (1953) is a hard-boiled pulp crime story full of suspense, sexual abuse, and vengeance, set in an urban underworld in which a vicious criminal element flourishes. The local mob boss, Matt Hagen, maintains an empire of gambling, prostitution, liquor distribution, loan-sharking, strong arm, and extortion. He threatens the protagonist, Chet Lawrence, because Chet has seen him abusing a woman he wants to “break in” as a prostitute. Eventually, Lawrence rebels from the community’s silent acquiescence to the “keep what you have” platitude that keeps Hagen in power.

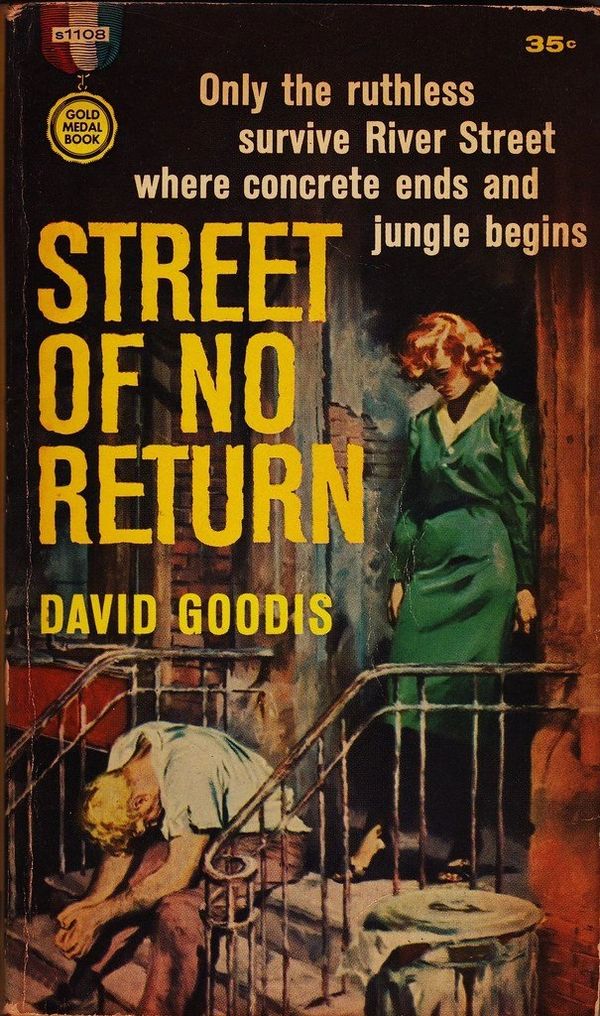

The companion novel to Street of the Lost, which had a similar cover, and a similar ending. "They sat there passing the bottle around, and there was nothing that could bother them." Street of the Lost: "Her next home was just a short walk across the street," Blurb (could be for both novels): "The Street Never Lets You Go."

Hagen and his gang invade Chet’s house, and when he returns, his long-suffering, loyal wife Edna is killed when Hagen throws her down a staircase. Then the entire neighborhood turns on the mob boss with an ice pick, a bread knife, and a can of lye. With Hagen’s death, the community is not liberated, but further shamed and morally enfeebled. Chet can only resign himself to the “facts on the ground,” with a new wife, in the same house that Hagen invaded. If he grows the backbone to revolt against the future mob boss, what would be the result?

An invaluable anthology. including stories and poems by Chris Offutt, Daniel Woodrell ("Joanna Stull," see below), Vicki Hendricks, Mark Turcotte, Esther Belin, and other icontermporaries. "Indreed the other America is Our America. It is the home of fractured dreams and failed ambitions. It is a war out there." (Lou Boxer).

The narrator in Woodrell’s “Joanna Stull” (in Stray Dogs, Writing from the Other America [2014]) has a father, Eugene, who is part of a gang of drug-dealing toughs who control the town. He has raped five women, taking their driver’s licenses so that he and his thuggish friends can terrorize them into keeping silent. The son observes Eugene’s latest victim: the blood, the swollen face, the vomit, the terror in her eyes. His “bones sweeten[ing] to the root,” he bashes Eugene’s skull open. One of Eugene’s motley crew implies there would be no retribution, that there was a fundamental rightness beyond the law, to what happened to Eugene. He goes on to say that most people’s “goody-goodness” would lead them to condemn the vengeance. “If they haven’t seen guts on the ground [the narrator is a decorated veteran], it’s just too frustrating to talk to them.”

Vigilantism is terrifying. But in the perspective of characters of some country noir protagonists, it provides some relief from helpless resignation. Where they live and work, elected legislators have not provided livable wages, accessibility of bank loans, institutional health care, or a relief from addiction to OxyContin. Eugene’s son’s vigilant attack on his father has a weird inevitability in such a social context.

This contrast between established “law and order” and a more primitive, ad hoc form of justice is further exemplified by Woodrell’s Winter’s Bone. The local drug dealers, who have murdered her father, allow her access to the body so she can provide authorities the fingerprints that confirm his identity. Doing so, she can claim title to the family house and raise her kids there.

Often, the habitus or social structure of the rural crime universe is not forever shadowed by an overarching worldview that makes any fight against it futile. While the difficulties of forging satisfying human connections are clear in rural noir, the possibilities of a progressive future can be in the offing

Copyright © 2022 Jay Gertzman, All rights reserved.

Rural v. urban noir. Response to "thou shalt not."

Rural v. urban noir. Response to "thou shalt not."

Copyright © 2024 Shooting Pool With David Goodis - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.